Ellen Smith: I was so interested to learn that you were a reporter for over twenty years before you began fiction writing. One thing I loved about Killing the Immortals was your ability to show many different points of view on a complicated issue. Do you think that working in journalism had an influence on your fiction writing style?

Jeff Haws: No doubt, and in all sorts of ways. One of the differences I realized early was when it hit me that there were no excuses anymore. Sometimes, in journalism, you're just dealt a bad hand. Maybe there's not much to the topic. Maybe the subject doesn't do much other than bite his lip and say "Uh-huh" a lot. But you do what you can with what you have, take lemons and make lemonades, all that stuff. What you, of course, can't do is make up quotes, or facts.

In fiction, though, you have to do exactly that. It was pretty freeing. Character isn't interesting? "Well, that's your fault, dummy. Make him interesting." I wrote mostly sports journalism, and the big thing that makes sports writing hard is you have the factual and structural expectations of news writing alongside the reader-entertainment expectations of music or feature writing. The reader wants to be transported back to the game they watched. They want to identify with the athletes they root for. So my writing is very story- and people-focused, because that's what journalism taught me. And now with fiction, I can make those stories and people whatever I want. It's freeing, but there's also pressure. If it sucks, well, that's completely on me. If I'm dealt a bad hand, I'm, ya know, the dealer. Hell, I can put the cards in whatever order I want. So, the groundwork is very different from journalism, but the goal is largely the same: write something that doesn't suck.

ES: When did you first consider a career in writing? Did you always see yourself pursuing both fiction and journalism?

JH: In eighth grade, I had this crazy English teacher named Mrs. Jones. She had been teaching 12th-grade English for 20 years, and this was her first year coming back to 8th; she had no interest in teaching us 8th-grade English. So she basically brought her 12th-grade curriculum and test ran it on us unsuspecting 8th graders. The first day of class, she walked in and told us she was "a slave driver." We all started looking for an exit. Maybe jump out a window or something? People would understand. But, yeah, she lived up to that. Toughest class I ever had—high school and college included. She had ridiculously high standards. She'd have us write papers on the books we read, and they'd go through two rounds of peer review, then two rounds of her reviews before we'd have a final draft. We'd never seen anything like it.

But ya know what? I learned. A lot. By the end of eighth grade, I knew how to break down a sentence. I knew prepositions and gerunds and semicolons and participles, and it made me enjoy writing. I'd worked my ass off for 4 Cs and two Bs in that class (I also had her for Reading class, where I also got 4 Cs and 2 Bs—I wasn't used to getting Cs, but she had no qualms failing people, so I took that and ran with it), and I was gonna put all that work to use, damn it. By the time I walked into my 9th-grade English class and quickly realized I already knew everything they were teaching me, I needed a new writing challenge. The school newspaper was down the hall. So that's when I knew.

As far as fiction goes, I never really expected to do that. I did start to write a Stephen King-derivative story (To be honest, I probably wished it could be Stephen King-derivative) called "Phobia" in 12th grade, but that was honestly the only fiction I'd ever written until I did a short story for a writing challenge with the local alt weekly about a year ago. I had decided I wanted to pursue fiction writing because it had a permanence I liked—whereas my journalism writing gets tossed in the garbage the day after I write it, no one can ever take a novel away from me—and I needed to create a new creative outlet as it had become harder to drum up freelance work lately. I had no idea how long it would take me, but my first goal was to just read as much fiction as I could get my hands on. I thought I might do that for a year to prep. But when I saw that writing contest, I decided to try it. And I found that...hey, I enjoyed it. And the story wasn't terrible. It didn't win, but it didn't suck. So I accelerated my plan a bit, and here we are.

ES: From journalism to freelance writing to fiction writing, you definitely live a creative life! In addition to writing, what other creative pastimes do you enjoy?

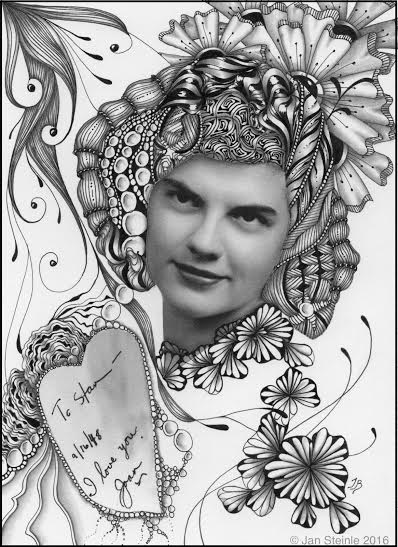

JH: All my creativity comes out in words. I've never really thought visually, from a creative perspective. Everything comes out in words. I don't draw or paint. I'd be lucky to put together a suitable stick figure family. But words pour out of me. I get backed up when I don't write. I can feel creatively plugged, like pressure needs to be released. At my day job, I do content marketing and social media strategy, so I do enjoy the creative challenge of using words to build a brand, and putting together a creative strategy that will help you reach the audience you intend to find—and working with those people who know more about visuals than I do.

I'm also passionate about all sorts of aspects of life that aren't all that creative, from baseball (Cubs fan since 1988) to newspapers to travel to craft beer, great food, classic film, music, religious philosophy, public transit, and grimy dive bars with sneaky-good beer lists.

ES: Both Killing the Immortals and Tomorrow’s News Today have original speculative fiction concepts. I imagine writing speculative fiction was quite a departure from journalism! How did you come up with your ideas?

JH: Killing the Immortals came out of a few brainstorming sessions where I came up with a bunch of ideas I wanted to flesh out. The basic concept was, "It's a stated goal of society and medical science to save every single life possible. So, what if we actually achieved that goal? What would be the ramifications?" Because, while it seems like an obvious goal on the individual level, reaching that goal would be completely disastrous on a societal level. I enjoy "What if?" stories, and what appealed to me about this one was, it's not all that outlandish. We are actively trying to do this, to whatever extent we can. So, I wrote out a long list of problems I saw coming from reaching this goal. When I reached "A cult would form around this going against god's plan," I knew I'd hit on something that could be a novel, especially with my interest in religious philosophy. There are lots more, though, and I'm toying with the idea of writing a series of books within this world. Not sequels, necessarily, but potentially incorporating some of the characters, and with the same basic premise.

On Tomorrow's News Today, that was the same brainstorming session. I wanted to write something about a journalist since I know and love that world so much. So I just started jotting down a sort of stream-of-consciousness page of thoughts that could turn into a story. I know this was an unapologetic "Twilight Zone" influence. I love that show so much. It being on Netflix makes my life better. And this was very much in that vein. If someone read Tomorrow's News Today and thought, "That reminded me of The Twilight Zone," I'd be very happy. Those stories were so often about a person receiving an unexpected gift of some sort, and seeing how it would change them. This story definitely looked at that.

ES: I’d love to know more about your writing process. How long did it take you to write your books? What was the process like for you?

JH: It's kind of funny to me now that Killing the Immortals only took me 6 weeks to write the rough draft. Started it Dec. 19 of last year, and I wrote the last word of the first draft on Jan. 31. That's 85,000-ish words in about 43 days. I sort of feel like that was an out-of-body experience. Then, for good measure, I wrote Tomorrow's News Today over the following 2 weeks, then a short story called The Trolley Problem in about a week in March, and then another one called The Slingshot—I think this is the best story I've written so far—in about 10 days in April. Clearly, I let the cork out of the champagne bottle, and words sprayed everywhere.

I try to write every weekday evening after work, for an hour. Since I can't—and don't want to—abandon my wife downstairs all evening every night, I don't really want to do much more than that. I think it's also good to set a time limit on yourself so you don't get too wound up in your own words and thoughts. I can usually knock out 1,200-1,500 words in an hour. Then, on weekend mornings, I typically wake up at 6, while she sleeps until 9 or 10. I'll write for a couple of hours on weekends or holidays, then read whatever book I'm on until she wakes up. I write straight through and do zero editing until two weeks after the draft is done. You can't make a good story great until you have that story to work with. I'm a big believer in getting that canvas down as efficiently as you can so you can start ripping it apart.

ES: Now I’m curious to know what projects you’re working on! Can you tell us anything about your current work-in-progress?

JH: Besides the final edits on The Trolley Problem and The Slingshot—I'd guess The Slingshot will come out on Kindle in January, while The Trolley Problem is probably set for March or April—I'm working on a story that still doesn't have a title I've liked. It's actually a massive expansion upon the short story I wrote for the local alt weekly's writing competition, and I'm approaching the 25,000-word mark. My hope is to finish it by the end of February, and have it out in the summer.

I feel like the scope of it is bigger than Killing the Immortals. More characters. More challenging concept. And I think it'll be longer. So it's been more difficult to write so far. The basic premise is that a virus rapidly wiped out a huge percentage of the world's population. Alessandra, a small town in North Georgia, was isolated enough for its citizens to avoid transmitting the disease, and they walled themselves off from the rest of the world. Audrey, Alessandra's leader, tells the people that the virus spread through human contact, and she requires everyone to wear a steel ring around their midsection in order to keep people from touching—all cohabitation or even having visitors to your home is banned. What are the psychological ramifications of this sort of forced personal isolation within a community? What will the people do to regain control over their lives? And what will Audrey resort to in order to protect the people of Alessandra while keeping her power?

ES: It was great chatting with you and learning more about your work! How can readers stay in touch with you through social media?

JH: As luck would have it, I'm really easy to find. I'm pretty much everywhere, and I love interacting with readers!

Twitter/Instagram: @byjeffhaws

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/byjeffhaws

Website and blog: http://www.jeffhaws.com